LAS VEGAS, NV – APRIL 28: Chairman and President of the Trump Organization Donald Trump yells ‘you’re fired’ after speaking to several GOP women’s group at the Treasure Island Hotel & Casino April 28, 2011 in Las Vegas, Nevada. Trump has been testing the waters with stops across the nation in recent weeks and has created media waves by questioning whether President Barack Obama was born in the United States. (Photo by David Becker/Getty Images)

By Steven Gan

One of the things that I have never been impressed with is a braggart, and to say that Donald Trump takes being a self-centered, narcissistic, egomaniac to the stratosphere is an understatement. Whenever he speaks, he manages to bring the conversation back to his wealth and how much he has accomplished. Sorry to get a little graphic, but statements like, “You know, I’m really smart;” “You know, I’m really really rich;” “I have a Gucci store worth more than Romney;” and the like make me want to vomit.

We’re all aware of Trump’s outrageous, insensitive, and illogical comments at the time he announced his presidential run about undocumented immigrants who come into this country by way of Mexico. There’s no question that all of us, regardless of our party affiliation, want to prevent people from entering this country illegally. But from what I’ve read, heard, and watched, the overwhelming number of people who enter this country illegally from Mexico—not only Mexicans, but also nationals of other Latin America countries—are trying to escape extreme violence and poverty. To characterize all of these desperate people, as Trump did, as rapists, drug dealers, and criminals is dehumanizing.

Many years ago, when I worked in our family business, I hired a young high school student as an intern. “Maria” was originally from Guatemala, and at the time that she began to work for us, I knew nothing about her background, and, honestly, I probably was not particularly interested. What I needed at the time was someone to help in the office, and this young girl came in like a whirlwind. She turned out to be a remarkable employee who ended up staying on with us for almost 20 years. One time I asked her what motivated her and her family to come to the U.S. She responded very simply, “We just got tired of all of the gangs, the killings, and the endless violence to which we were continuously subjected.”

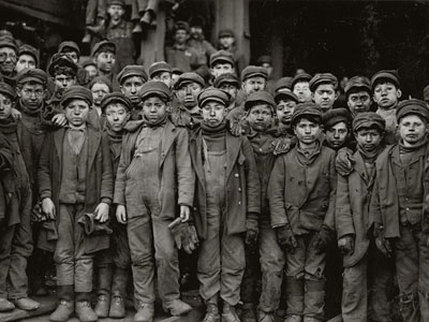

Here’s Maria’s story: When she was 10 years old (about 1974), Maria ‘s mother took her and her seven-year-old brother away from Guatemala on the El Norte highway (a series of trains from Central America all the way to the Mexico-U.S. border where most of the hopefuls ride on top of the freight cars), hoping to reach the U.S. On the way, they were robbed, beaten, and even pistol-whipped. Once they arrived in Tijuana, they found very menial work for a few months and saved enough money to pay a coyote to take them and some others through an unchecked border area. The coyote left them at the point where they had to crawl through a mile-long sewer pipe until they reached the U.S. side of the border. During their harrowing trip through the excrement-and- vermin-filled pipe, they were bitten by hundreds of rats, not just on their bodies but also on their faces and hands. As Maria described it, the rats “just kept coming and coming.”

The idea of crawling on my belly through a mile-long sewer pipe and enduring attacks by hundreds of rats along the way is more frightening than any horror movie I’ve ever sat through. If that’s not enough to send someone into a psych ward, I just don’t know what would be.

When Maria, her mom, and her little brother finally made it through the pipe to the U.S. side of the border, another contact was waiting for them who took them to the jefe’s (big boss’s) house in southern California. For the next few years, they picked oranges, avocados, and other crops on a series of farms. They were often not paid their full wages (or not paid at all). And, of course, they never complained—for fear of being cast out and deported. Apparently, this hard life on the very fringes was still better than what they had left in Guatemala.

Fortunately, Maria’s mother had a distant cousin in Chicago, where they eventually moved and settled. The cousin helped Maria’s mother get a job with a cleaning service and arranged for Maria and her brother to start school. From that point forward, their lives turned a corner and they settled in.

Sometime during the early ’80s (when Maria started working for us), a general amnesty was granted by the government to all undocumented immigrants who could prove that they had been living in the U.S. for at least five years. For Maria, her mother, and her brother, this was their lucky opportunity to move out of the shadows and into the daylight of living normally in America. Some years later, they all became American citizens. Maria’s brother joined the military and even fought in the Gulf War.

Now, I’m not advocating wide open borders, but how many people do you know who share Maria’s story? Although I only know Maria’s first hand, I’m sure there are millions like her who have endured similar struggles, putting their lives on the line (and in fact many do die each year trying to cross the border) to get into this country to make a better life.

For me, it comes down to trying to reconcile our immigration system with compassion toward other, less fortunate human beings.

Do you think Donald Trump knows any undocumented immigrants who, like Maria, endured life-and-death struggles to get to this country? Trump’s self-aggrandizing rhetoric, along with his empty threats to make Mexico pay for every “illegal alien” that he irrationally claims the Mexican government sends to the U.S., leads me to believe that he couldn’t care less about anyone but himself, let alone the poor and unfortunate on this planet who only want to work, be safe, and provide for their families. I’m forced to conclude that compassion towards those “illegals” who pick our nation’s fruits and vegetables, clean our office buildings, and perform many of the menial and dangerous jobs in our country is not an asset that is included in Trump’s financial statement.